FlareonzVerse

I'm written in c++

Dev Journey: Dynamic terrain chunk loading

Flareonz44 - June 19 2024

When I decided that my game had to be in 3D and have infinite terrain, the first problem I encountered was how to load the terrain in parts, as loading it all at once would cause serious performance issues. Despite my search, I found very little information on how to implement this or even how it is implemented in other games like Minecraft, so my last option was to design my own dynamic loading system.

The basic idea

The idea is quite simple: I want a program that automatically loads the chunks around the player as they move along the X and Z axes. However, it’s not that simple. While it sounds easy to say, I sensed there was a hidden complexity behind it. And I was right.

Algorithm logic

I will try to explain the logic and how I put it together. This isn’t an implementation in a specific language; the scripts are in Python, but the idea is that you can understand the logic and port it to your favorite language.

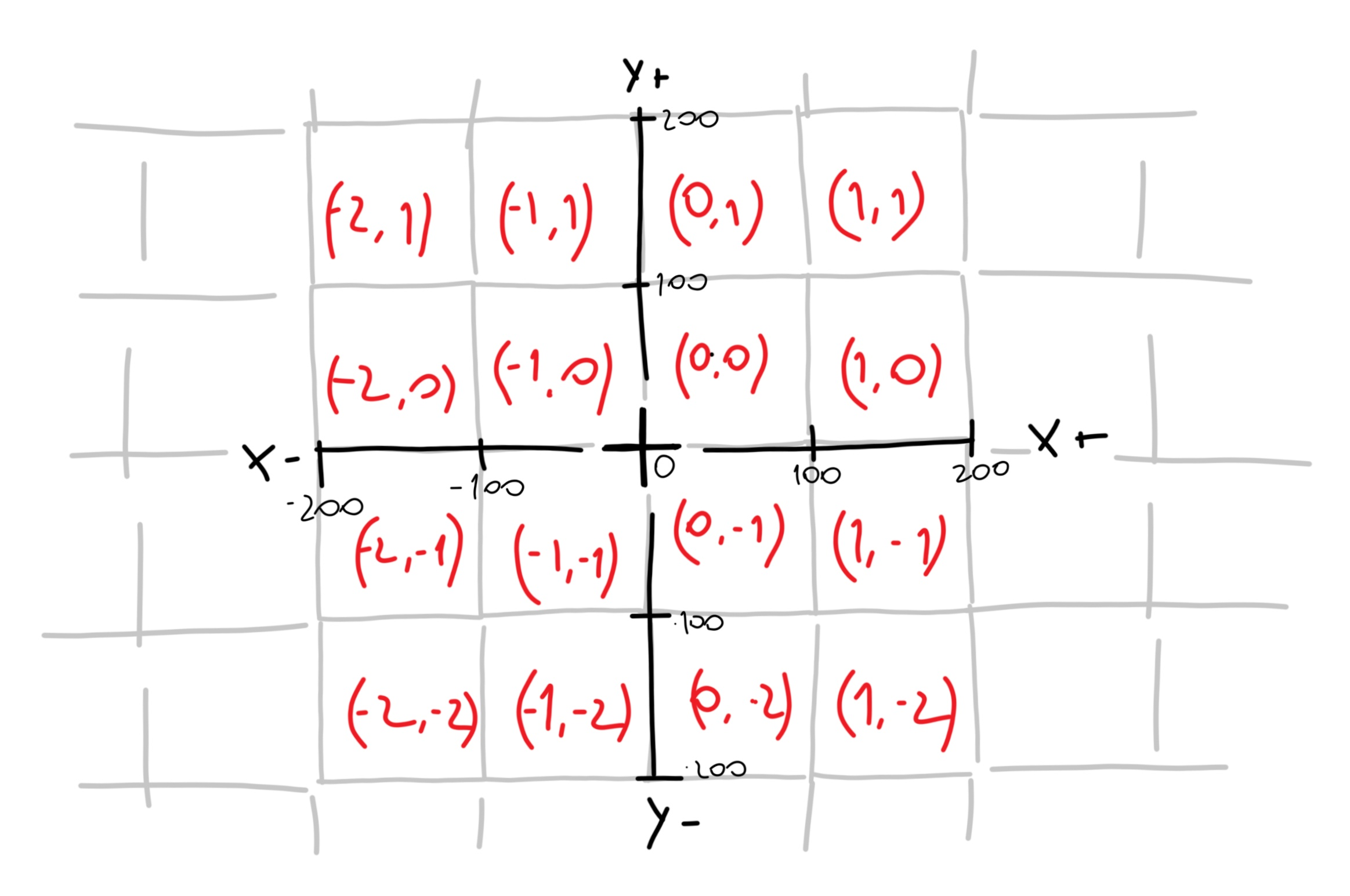

To have a dynamic loading system by chunks, we need to establish some parameters to work with. The first thing we need is a way to divide the space into portions. Suppose we want our chunks to be 100x100 meters (we’ll say that 1 meter is a unit of the axis. For example, if we move 10 units in the X direction, we’ll say we moved 10 meters in X to make it easier to understand). Now, we can build a function that allows us to calculate which chunk the player is in given their coordinates in the world. We will create a coordinate system of chunks using integer values. For instance, the chunk (0, 0) is the chunk that spans world coordinates (0, 0) to (100, 100). The chunk (1, 0) will span from (100, 0) to (200, 100).

In the diagram, world coordinates are represented in black, and the coordinates of each chunk are written in red.

For creating this function, we will use a mathematical function known as integer division. Unlike traditional division, integer division returns the integer value of the result, without the decimal part. By dividing the given coordinates by the size of the chunk, we will obtain the position of the chunk in the integer part. In the following script, you can see the implementation in Python.

def get_chunk_coordinates(x, y, chunk_side):

return (x//chunk_side, y//chunk_side)

And why do we need to do this conversion? Because we are going to use the chunk coordinates to determine where to place the 3D model of the chunk in the world coordinates, among other things that I will reveal later.

Now that we have saved the coordinates of the chunk the player is in (or any other entity or set of coordinates we pass as a parameter), we also want to know which chunks to generate around him so that the player has a complete view of their surroundings.

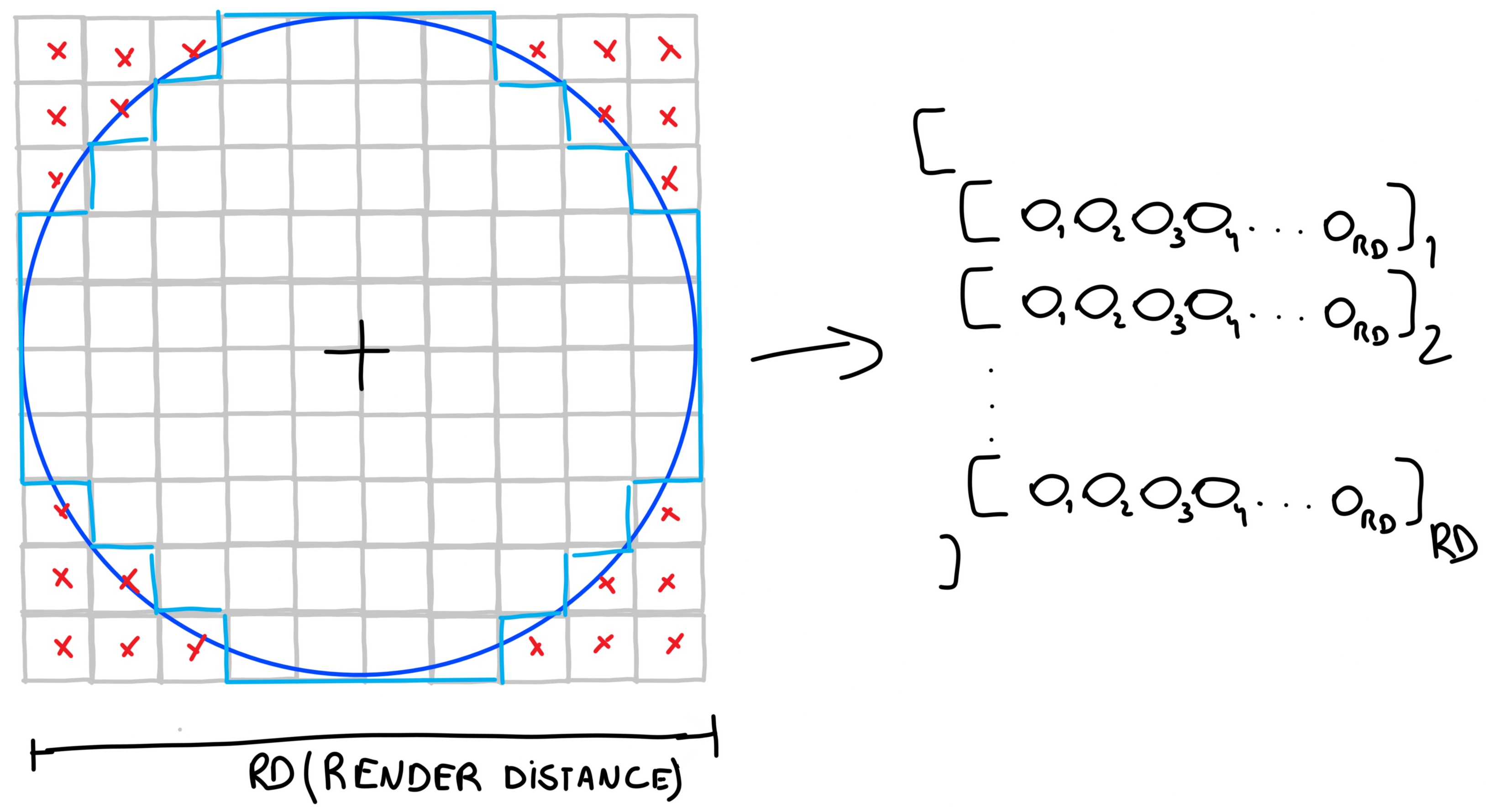

To achieve this, there are many methods, but I will explain the one that seemed to me the best option. We will generate a two-dimensional list and then, with some trigonometric calculations, we will be able to obtain a reference that will help us calculate the exact chunks we should load. The nice thing about my implementation is that it supports any render distance values, which can be very useful for certain games. We set our chunk rendering distance to be 500 meters, or 5 chunks. Since we want the chunks to be rendered in a circle around the player, we will say that 5 chunks will be the radius of that circle. Therefore, we will create a matrix with a side size of 2 * render_distance, in this case, a 10x10 matrix. In my case, I’m going to fill the matrix with “O” just to have some content. In the diagram, you can see an outline of this idea. The size of the matrix is determined by the rendering distance measured in chunks. Then, we draw a circle and see that the chunks inside the highlighted area are the ones that should be rendered, while those in the corners (marked with a red X) should be discarded. But how do we achieve this for a N-size matrix?

To do this, we need to iteratively go through all the rows and columns of the matrix, using one for loop inside another, with variables I and J respective to each loop, which we will use as coordinates. We need to center these coordinates, as the loops run from 0 to a certain number N. For example, in our case, we want the ranges to start from -5 to 5 instead of 0 to 10, so we will subtract RD to our I and J values. We will save this centered values in another variable called CC.

Now that we have this centering done, we can start drawing our circle. How? Each iteration for each row and column will have a centered coordinate associated with it. Since we know the center is at (0, 0), we can calculate the distance from CC to the center using the Pythagorean theorem. With this data, we apply a threshold: if the distance is above the threshold, the chunk will be discarded; if it is within the range, we will take the modified coordinates and add them to the player’s chunk coordinates at that moment. This result is added to a list, and after iterating through all possible values, we will have a list with all the coordinates of the chunks that we must generate so that they are created around the player in a circular form.

Finally, you are ready to use to values for your needs (generate terrain, load certain models, etc).

def get_generation_chunk_list(player_x, player_y, chunk_size, render_distance):

pla_chunk_pos = get_chunk_coordinates(player_x, player_y, chunk_size)

circle_matrix = [["_" for _ in range(render_distance*2)] for _ in range(render_distance*2)]

chunks_to_be_loaded = []

#for i in circle_matrix: # \ with RD = 2, _ _ _ _

# for j in i: # | this code will _ _ _ _

# print(j, end=" ")# |---> print this ---> _ _ _ _

# print() # / _ _ _ _

for i in range(render_distance*2): # i for Y

for j in range(render_distance*2): # j for X

cc = (i-render_distance, j-render_distance)

distance_to_00 = math.sqrt(abs(cc[0]+.5)**2 + abs(cc[1]+.5)**2) # V(c^2 + c^2)

if distance_to_00 < render_distance*.95: # .95 is the shape threshold

circle_matrix[j][i] = "O"

chunks_to_be_loaded.append((pla_chunk_pos[0]+cc[1], pla_chunk_pos[1]+cc[0]))

#for i in circle_matrix: # \ with RD = 2, _ O O _

# for j in i: # | this code will O O O O

# print(j, end=" ")# |---> print this ---> O O O O

# print() # / _ O O _

return chunks_to_be_loaded

# testing

load_list = get_generation_chunk_list(655, 533, 100, 5)

print(load_list)

There are several important aspects to highlight about the code above.

First of all, circle_matrix is a 2D list that contains only underscores (_). This is used only to display how the 2D matrix behaves and to show the final result. You can safely omit all the print statements and focus only on the calculations.

Then, you probably noticed that in the distance_to_00 variable calculation, I used abs(). That’s because we cannot pass negative values to the power calculation, and since negatives do not affect the math here, it works. I also added 0.5 to each side on the length calculation, to address an offset issue. Basically, every time you do the CC subtraction, you will always have an offset of 1, mainly because of the even-length nature of RD*2. So, we virtually apply this offset to patch that problem.

Finally, I added a shape threshold, which will help me shape better the circle form, mainly to fix some visual issues (just to achieve some kind of pixel-perfect-shape).

Dynamic loading

So far, we have the most basic setup, as it only generates the chunks around the player. However, we also want the terrain to load dynamically as the player moves, ensuring a circle of loaded chunks around him at all times.

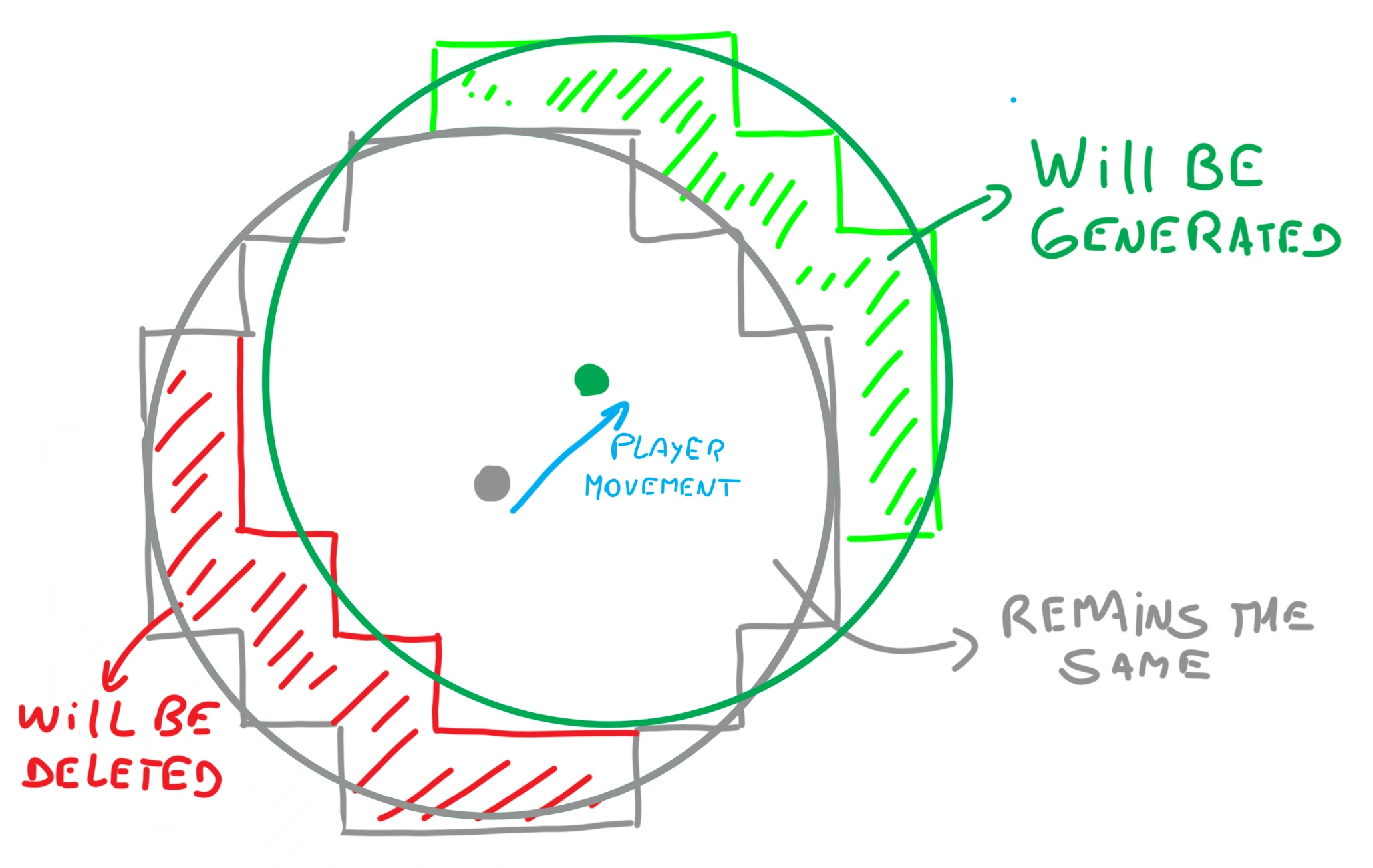

To achieve this, every time we generate a chunk, we will add the pair of XY coordinates of the chunk to a special list, allowing us to keep track of what we’ve generated. We will constantly evaluate how far the player is from the center point of the generated circle. If the player exceeds a threshold we set, we will run a function that generates the necessary chunks for the new position. We will generate the matrix again and calculate all the chunks to be generated, but this time we will check if the chunk to be generated is already in the previously generated chunks list. If it is, it will not be generated; if it is not, it will be generated. Finally, we will iterate through all the chunks generated in the previous instance, and if we find XY pairs that are not in the new generation range, they should be eliminated. The diagram shows how it works: the area marked in red is eliminated, those marked in green are added, and what is kept in gray will be omitted, as it was already generated before.

In this way, we avoid unnecessary problems and make subsequent generations faster by omitting previously generated chunks instead of having to generate everything again over and over.

chunks_loaded= [] # here we will sabe all rendered chunks

dst_to_circle_center = calculate_distance(player_position, circle_center) # distance from player to circle center (in meters or units)

if render_order or dst_to_circle_center > 200: # render_order just if we want to force the chunk loading

circle_center = get_chunk_coordinates(player_x, player_y, chunk_size) # update the center, so it works for the next time the player goes further than the circle center

load_list = get_generation_chunk_list(player_position[0], player_position[1], 100, 5) # chunks to generate / load

for chunk in load_list: # generation process

if not chunk in chunks_loaded:

render_chunk(chunk) # a function to create the chunk, either by generating it ot loading from 3D model

chunks_loaded.append(chunk)

for chunk in chunks_loaded:

if not chunk in load_list:

unload_chunk(chunk) # a function to remove the chunk from the render view and from memory

chunks_loaded.remove(chunk)

Applications

This algorithm is very simple and can be applied to any game engine or framework. If we have a very large map, we could split the model into perfect square chunks and use this system to determine which areas we should generate. In my case, since the terrain generation is procedural, I use these chunk coordinates to calculate the coordinates of the noise map, ensuring that the generation across chunks is smooth and fits perfectly.

Conclusion

Dynamic loading is not only a key component for the optimization of large 3D spaces, but it also gives us the possibility to create infinite spaces using procedural generation. Although my algorithm may not be the most efficient, it works and intuitively allows us to understand what is happening in the backend so that the terrain appears, to the player’s eyes, always fully loaded.

See ya!